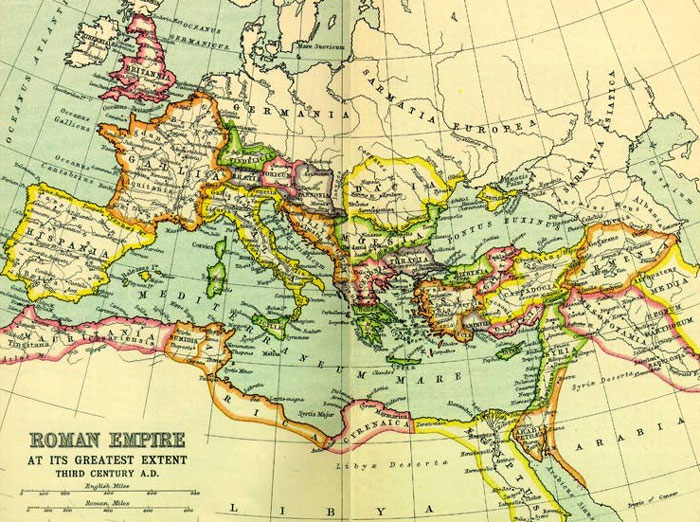

753 to 30 B.C.

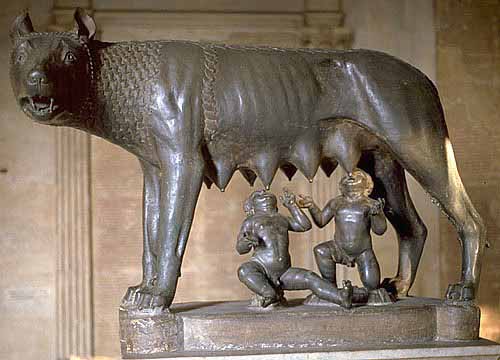

A. The Legend of Romulus and Remus

- According to legend, the orphaned brothers Romulus and Remus founded the site that would become Rome around 753 B.C. These brothers were wild by nature and had been raised as babies by a she-wolf who found them by the side of the Tiber River.

- Romulus and Remus fought over who should rule Rome. As you probably guessed by the city’s name, Romulus won by killing Remus. This would just be the beginning of Rome’s amazing, yet bloody, history.

B. The Probable Beginning of Rome

- By 1,000 B.C. Italic tribes had settled most of Italy. As many years progressed, these tribes formed into small farming villages. By 800 B.C. the Italic tribes had neighbors to the north and south. In the north a mysterious people called the Etruscans moved in and claimed Tuscany as their own. Etruscan origins have been a mystery to historians. It is clear from the archaeological evidence that they were not related to the Italic tribes, and their language was not Indo-European. Genetic evidence seems to indicate that the Etruscans came by sea from what is now modern Turkey.

- To the south, several Greek city states had been established, many with ties to the powerful Greek city states in Greece. As you know, Greeks settled all over the Mediterranean. Greek settlers left Greece when their native cities became over crowded.

- The Etruscans decided to conquer the tribes in mid-Italy (Latium) where Rome was/is situated. Rome was a village of mud huts built around the Palatine Hill near the Tiber River when the Etruscans came.

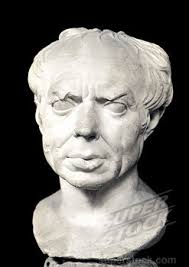

- The Etruscans civilized the Romans and turned Rome into a small city made of brick. Several Etruscan kings ruled the Italic cities. The Tarquin aristocracy ruled Rome.

The Etruscan Impact on Rome

A. Originators of Roman Greatness

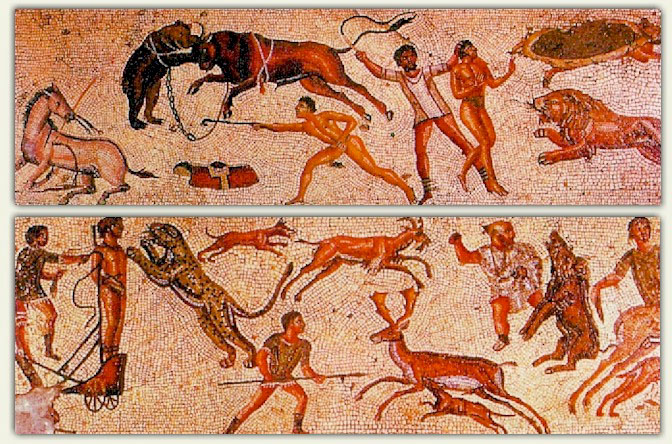

- Romans learned from the Etruscans many of the skills for which Romans would become famous. Etruscans gave the Romans their alphabet, the knowledge of building the arch, (without which the aqueducts could not have been built) the military legion, and gladiatorial combat.

- The last Roman Etruscan king, Tarquin the Proud, was very disliked. According to tradition, his son raped Lucretia, a model Roman woman. She told her husband and then killed herself. The Roman public went nuts. Led by the Roman, Brutus, they fought and

killed any Etruscan they could get their hands on. Romans successfully expelled the Tarquins out of Rome in 509 B.C., but it would take about another 200 years (about until 350 B.C.) before the Etruscans were whipped in Italy. Meanwhile, the Romans had serious domestic issues (very unhappy Plebeians), their fellow Italic neighbors, and Greek city-states to worry about.

killed any Etruscan they could get their hands on. Romans successfully expelled the Tarquins out of Rome in 509 B.C., but it would take about another 200 years (about until 350 B.C.) before the Etruscans were whipped in Italy. Meanwhile, the Romans had serious domestic issues (very unhappy Plebeians), their fellow Italic neighbors, and Greek city-states to worry about.

Let’s Hear it for the Republic!

A. Roman Government—Republic Style

Video: Patrons and Politicians

- The Roman Republic was founded in 509 B.C., but it took a long time before Patricians and Plebeians were willing to work things out (or rather until the Plebeians finally settled). From about 470 B.C. to 287 B.C., Patricians and Plebeians fought each other for political control. From then on their assemblies fought it out.

The Struggle of the Orders (A.K.A. The Social Classes Fight for Power)

- At some point in the mists of time, Rome established its original to social classes: the Patricians and the Plebeians, or Plebs. According to the ancient Romans, the original Patricians (Who get their name from the Latin word, pater, which means “father.”) were from the families of the first Senators. These Senators were chosen by King Romulus himself. He chose one senex (old man), from 100 powerful families. They became his advisers.

- Later Patricians were men chosen by one of the Tarquin kings for their wealth and political power. Anyone who wasn’t a Patricians was a Plebeian. This meant the vast majority of Romans were Plebeian.

- Patricians thought it was their birthright to rule. They saw themselves as superior to the Plebeians and the only people capable of ruling.

- Plebeians (for good reason) thought many Patricians were wicked, greedy, socialites, who sought to rule solely at Plebeian expense. Indeed, Patricians did take advantage of Plebeian farmers, some to the extent of forcing Plebeians into slavery!

- The Patricians seemed to have all the cards, but the Plebeians did have one collective ace up their tunics—not only were Plebeians the farmers, but they made up the entire army’s infantry! Early Rome believed in a citizen army and relied on the Plebeians to be soldiers in times of need. One day, just as tribe of barbarians was approaching, the Plebeians suddenly refused to serve. The Patricians knew they had to share some of the power. By roughly 287 B.C., the Roman Republic would be in its permanent form until the time of Caesar.

Government Positions of the Republic

A. Consuls

- Two consuls were elected as head of Roman government. One of them had to be a Plebeian. Consuls presided over the Senate, the Assemblies, created and enforced laws, served as generals, and represented Rome in foreign affairs. Consuls served for only one year. In times of military emergency, a consul could serve for six months as military dictator.

B. Praetors

Eight praetors served as judges in law courts. They often assigned private citizens (Patricians most likely) to judge over some the more numerous and less serious cases. To be assigned to serve as a judge was an honor. It was expected of every nobleman to practice law as a civic duty, not for pay.

Eight praetors served as judges in law courts. They often assigned private citizens (Patricians most likely) to judge over some the more numerous and less serious cases. To be assigned to serve as a judge was an honor. It was expected of every nobleman to practice law as a civic duty, not for pay.

C. Censors

- Two censors revised the lists of Senators and Equestrians. Censors conducted a census of the citizens, did property assessments for tax purposes, and granted state contracts. Censors also kept an eye on the moral conduct of the populace and could expel Senators who behaved badly.

D. Aediles (ee dials)

- Four aediles supervised public places, public games, and the grain supply into the city.

E. Tribunes

- Ten tribunes served to veto any act that was harmful to the Plebeians. The office of tribune was created by the Plebeians in order for someone to be looking out for their interests. Tribunes had to be Plebeians themselves. Anyone who tried to harm a tribune could be executed immediately.

F. Quaestors (quee stors)

- Twenty Quaestors served as treasurers and looked over the finances of the Republic. A man who served as a quaestor was automatically eligible to serve in the Senate with the okay of the Censors.

G. None of these were paid positions. However, that didn’t mean a politician couldn’t get rich while in office. All these positions were open to men only.

The Senate

A. Composition

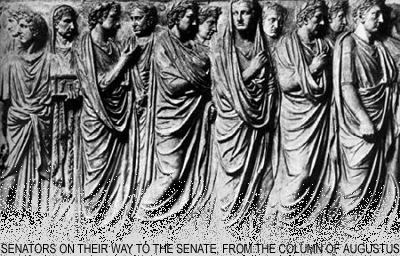

- Senators belonged to the best noble families in Rome. During the Republic, the Senate consisted of officials and ex-officials totaling about 300 men. They could not become part of the Senate without approval of the Censors.They met to discuss matters of state in the Curia Hostilia, which was located in the Forum.

- The Senate was technically only an advisory board. Senators were merely supposed to give their advice on matters of state. In reality, nothing was done without Senate approval, since the Senators were the wealthiest and most powerful men in the Republic. Since they had most of the money, they ultimately controlled the military, and passed decrees that the Assemblies were expected to accept.

- SPQR (Senatus Populusque Romanus), meaning The Senate and the People of Rome, were the letters that symbolized the Roman Republic.

The Assemblies

A. Composition

- The Assemblies were composed of all males who were full Roman citizens. Individuals had to attend in person to vote on legislation. Votes were counted in groups, not individually.

B. Assembly of Centuries

- The members of the Assembly of Centuries elected consuls, praetors, censors, declared war, and served on the court of appeal for those citizens sentenced to death. Membership was determined by individual wealth.

C. Assembly of Tribes

- The assembly of Tribes elected all other officials. They voted yes or no on laws. Membership was originally determined geographically and then later passed on by birth. After 287 B.C. their laws pertained to all Roman citizens.

Political Interest Groups—Yes, the Romans Had Them Too

A. Two Political Interest Groups—The Populares and the Optimates

Video: Roman Cities

- The Populares was the interest group of the people. Its power base was among the Assembly of the Tribes. It was liberal. Some Senators belonged to it.

- The Optimates was the interest group of the nobles. Its power base was in the Senate. It was conservative. Its interests lay with the wealthy and noble families.

- The Optimates and Populares should not be considered to be the same as modern political parties. They weren’t as complex. Basically, a conservative official alligned himself with other like-minded officials who belonged to the Optimates. A liberal official would allign himself with other liberal officials who belonged to the Populares. It’s that simple.

B. Campaigning for Political Office

- A candidate for office received no financial backing from the state. Therefore, candidates had to be personally wealthy. Showmanship and generosity to voting masses was essential.

The New Roman Social Classes (2nd Century B.C.)

A. The Senatorial Class

- This class was composed of Senators and their families. Patrician-nobles dominated it.

B. The Equestrian Class

- This class was composed of people who could afford it. These people were not senators but very wealthy nonetheless.

C. Commoners

- This class composed the largest citizen class with full rights as citizens. These people were poor to low-middle class farmers, artisans, minor officials, and merchants.

- Under the commoner class there was an extremely large group of citizens known as the “capite censi”, or the Head Count. The Head Count were the poor masses who made up Rome’s slums (in an area known as the Subura). The Head Count had almost no politcal power. This would change slowly after general Marius had the audacity to recruit them for his army. Before Marius’ recruiting of the Head Count, only citizens with property could serve in the military.

D. Freed People

- Freed People belonged to a class of former slaves. They were considered citizens (if their former owner was a citizen) but did not have the full rights of a citizen. Also, Freed People were obligated to serve their former masters in some capacity. The children of Freed People were full citizens with the full rights of a citizen.

E. Slaves

- Slaves belonged to lowest class and were considered little more than property. Slaves came from all over the lands conquered by Rome and were not chosen by ethnicity.

Spartacus and the Great Slave Revolt 73—71 B.C.

A. Changes in the Republic

- As Rome grew into an Empire, slaves poured into Rome and all around Italy. In 73 B.C., Spartacus, a Thracian who had once served as an auxiliary to the Roman army, revolted from the gladiator-slave school he was in along with 70 to 80 gladiators.

- Slaves from large plantations left their masters and joined Spartacus’s army. Eventually, the slave army grew to 120,000 men. These men were well trained by Spartacus and the former gladiators who escaped with him.

- Spartacus was looking for a way out of Italy. Unfortunately, his fellow Gaul and German leaders wanted to stay and plunder the Roman countryside, leaving Spartacus little choice but to split his forces.

- Had they all stuck together, perhaps the army would have made it. Spartacus proved to be a skilled leader, and his army destroyed legion after legion. Had he wanted, Spartacus might have captured Rome itself, because the Senators were slow to realize the danger he posed.

- Eventually, the richest Roman in town, Crassus, was given leadership of the Roman army in Italy. Crassus had enough military sense to eventually beat Spartacus.

- Spartacus’s body was never recovered. So many bodies littered the final battlefield near the Siler River in southern Italy, that it was impossible to recover his body.

- Six thousand captives from Spartacus’s army were crucified from Rome to Capua (where the gladiator school had been) along the Appian Way— Rome’s most traveled road. The bodies were left there for weeks to rot in the sun.

Roman Religion and Philosophy

A. Greek Influence and the State Religion

- Rome had a state religion that it expected people to follow to some degree. Romans were always very tolerant of other religions and absorbed gods and practices from the people they conquered.

- By 217 B.C. the Roman and Greek gods were considered to be on equal footing, just having separate names in most cases.

- One of the most important of the goddesses was Vesta, the goddess of the hearth-fire, and center of the Roman house. Her popularity was not surprising since Romans placed a high value on family life.

- Special priestesses called the Vestal Virgins watched over the sacred fire in the temple to Vesta, which was located in the Forum. They lived in the Forum in the Atrium Vestae. No men were allowed to visit them privately except for the Pontifex Maximus—the head priest among priests.

- Romans had many priests. The most important were the Pontifices.

- Rome’s most important temple was situated at the Capitoline Hill and was dedicated to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

B. Mystery Cults

- Roman soldiers came into contact with many foreign religions. Two mystery cults (so called because many of their rites were kept secret) were the Isis and Mithras cults. The cult of Isis originated from Egypt and the cult of Mithras originated from Parthia (the name for the land controlled by the Persians—not related to Darius, Xerxes, etc.). Mystery cults were looked down upon and sometimes suppressed.

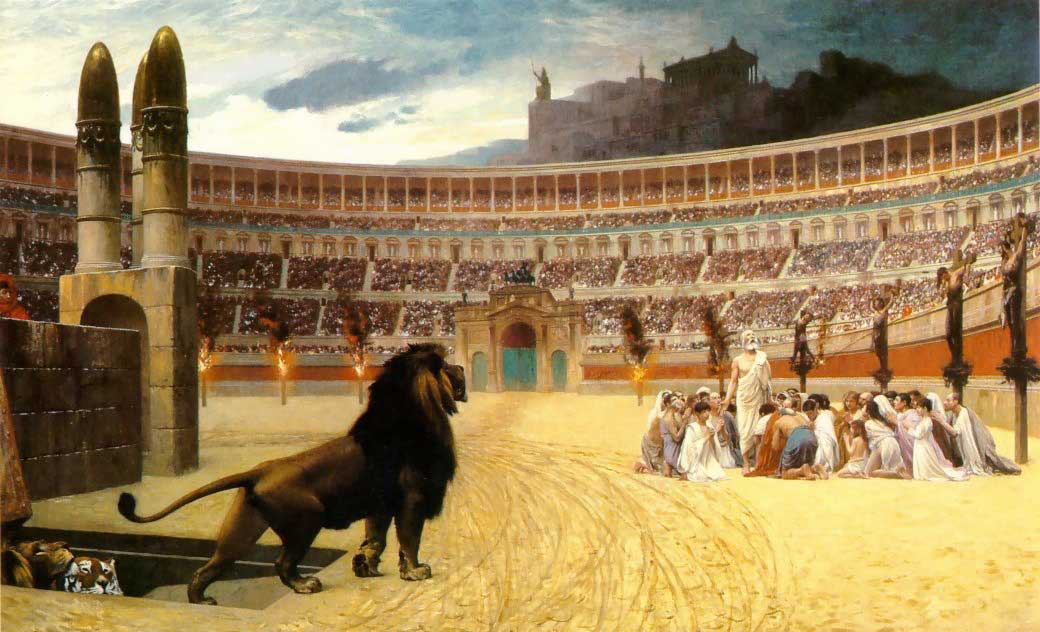

C. Christianity in the Roman Empire (not Republic)

Video: Constantine Becomes Emperor

- Christianity’s origins started from a small movement of disciples in Judea who followed the teachings of Jesus Christ and worshipped him as the son of God.

- Christ’s followers were excellent teachers of the new faith and taught about the life and teachings of Jesus Christ in stories called gospels. “Gospel” is an old English word that means “good tale” or “good news.” After Jesus’s death, there were several gospels told by early Christians, but eventually only four would be accepted into the New Testament of the Bible. These are the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The gospels each tell stories about Jesus and his 12 Apostles. The Apostles were the main followers of Jesus and helped him teach his message.

- In a very short while, Christianity started to spread across the Empire into Rome itself. The Empire had numerous, well-maintained roads. These roads were protected against brigands and thieves. This meant relatively easy travel for teachers of the new faith to spread the word of Christ across the Empire. The most notable of these teachers was Paul. He converted thousands to Christianity and was chiefly responsible for allowing gentiles (non-Jews) to become Christians.

- At first Roman rulers were very tolerant of Christians. They thought Christianity was merely a sect of Judaism and had before learned to tolerate (somewhat) Jewish refusal to follow the state religion of Rome.

- By that time, one of the few religious rules the Emperors of Rome insisted upon was the act of worshiping them as a god. It was seen by Romans as their patriotic duty to worship their emperor as a god—tantamount to Americans saying the Pledge of Allegiance. The Romans by then (for the most part) exempted Jews from worshiping the emperor, but when it became clear that Christians were not only made of former Jews, but of many people across the empire, Rome turned a suspicious eye toward Christianity.

- Eventually, Christianity was classified as a mystery cult—something many Romans tended to suspect for doing weird stuff. Many Romans seriously misunderstood the early Christians. Christians were thought to be magicians, performing bizarre rituals that included cannibalism! Of course, none of that was true, but gossip never helped anyone, and it became disastrous for Christians.

- Whenever hard times hit Rome, conservatives blamed the influence of non-traditional Roman values for the problems. Often, Christians were blamed because they behaved in “un-Roman” ways. Like Jews, Christians also refused to worship the emperor and often would not serve in the military.

- Weak, and sometimes crazy emperors, such as Nero, looked for scapegoats to blame for their own ineptitude. Unfortunately, the scapegoat often chosen was the Christians. A catastrophic fire in 64 A.D. ruined most of Rome’s poorer sections. Many Romans suspected Nero of having his henchmen start the fire so he could clear the land needed to build his new palace. He needed a scapegoat and fast! He chose the Christians of Rome.

- Nero had thousands of Christians murdered. Paul may have been killed in Rome at this time. Many were torn to pieces by wild beasts in the arena for public enjoyment. Hundreds were crucified there too. The Apostle Peter was said to have been crucified upside down. In an ultimate act of depravity, Nero had Christians strapped to posts and covered with pitch to serve as torches to light the city of Rome.

- At first the Roman Mob enjoyed the spectacle, but many began to feel sorry for the Christians. When they saw how bravely the Christians died, many began to doubt Christians were responsible for the fire. Nero didn’t last much longer. He eventually committed assisted suicide when he heard the Senate had ordered him to be flogged to death.

- Although Christians would suffer by the hands of other emperors, (especially Diocletian) their popularity continued to spread. What made Christianity so appealing to the ancient world was its acceptance of all people, regardless of class or gender. Rich or poor,

Senator or slave, man or woman—all were accepted. The message of a better life in Heaven, compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness, patience, and turning the other cheek, also gained many converts.

Senator or slave, man or woman—all were accepted. The message of a better life in Heaven, compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness, patience, and turning the other cheek, also gained many converts. - Eventually, in 313 A.D., the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, making Christianity the official state religion. In 391 A.D., the emperor Theodosius made Christianity the only legal religion of the empire. The sacred fire in the temple of Vesta was extinguished after burning for hundreds of years and the Vestal Virgins removed. Now pagans (non-Christians) were persecuted. The tables had turned.

D. Stoicism: The Philosophy of the Elite

- One philosophy/religion that gained wide acceptance among Rome’s elite was Stoicism. Stoicism was a philosophy/religion started by the Greek philosopher Zeno (336-264 B.C.). Zeno was an admirer of Socrates and appreciated the way Socrates chose death rather than give up his morals.

- Human virtue for Zeno could only be found in the internal thoughts and values of a person.

- Stoics were fatalists—meaning they believed they had little control over external forces. For them whatever happens, happens. The only thing man had control over was his own judgments. Since everything else (including the acts of others) was not within his/her power to control, Stoics sought to feel indifference.

- Stoics were accused of being cold and unfeeling. In fact, today when a person behaves without emotion, he/she is said to be acting stoically. There may have been some merit to this accusation. However, Stoics sought to control their passions, not all emotion.

- Stoicism was popular among many of the Roman elite, including Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

The Roman Military

A. The Legion

- The legion was the basic unit of Rome’s standing army composed of career soldiers called legionaries. Legionaries were originally drawn from the farming-Plebeian sections of Roman society, but through the reforms made by Marius, the Roman army became composed of professional soldiers.

- Legion sizes varied but consisted around 4,300 men. Each legion was split into ten basic fighting units called cohorts. The first cohort also had some non-fighting men in its service—clerks, engineers, and other military specialists. Each cohort consisted of around 424 men, plus six centurions. Each centurion was a professional fighting commander who gained his position through military service, not political appointment. They did not belong to the Senatorial or Equestrian classes. Centurions controlled a unit called a century that despite its name, did not usually have exactly 100 men in it (usually around 80). Centurions had the heavy responsibility of disciplining their men and making sure orders were followed during the chaos of battle. Centurions were the glue that kept the legions together. To lose a centurion in battle was a devastating blow. A centurion was recognized by the crest on his helmet: it went left to right, instead of front to back. He also wore greaves.

- Crests were often used to help distinguish rank. A general’s crest and his officers’ (Tribunes or Legates) went front to back and could be distinguished by their color and by the material from which the crest was made (horse hair, feathered plumes, etc.) A regular soldier did not wear a crest unless on parade. Auxiliary soldiers (soldiers outside the normal infantry) usually had differences in their military dress too, to set them apart in function and rank.

B. Generals

- Each military campaign had one general assigned to it. This did not change until imperial times, since Rome was at war in different territories constantly.

- A general was always a Patrician of the Senatorial class. He was usually a consul, proconsul, or even ex-consul (later in the Republic’s history) and had to at least have the rank of Praetor in public life (They had to be at least judges). Always remember that in Rome’s history, the military life and the public life, could not readily be separated—and were not separated while on campaign or in the provinces.

- The general had to be given imperium, or the right to command, by the Senate.

- Generals and other officers wore Greek style armor that imitated a muscular chest. Generals also wore cloaks colored purple. Purple was an almost sacred color reserved for only those members of Roman society who were of the very highest rank.

C. Legates and Military Tribunes

- Although generals commanded several legions, each legion had its own commanding officer who served directly below the general. These officers were called legates. Under each legate were six military tribunes.

- Generals gave orders to his legates and tribunes directly. The legates made sure the tribunes carried out the orders to the legions. Centurions received the general’s orders from the military tribunes, and the centurions made sure his century followed orders.

D. Marius’s Mules (And the Path to Emperor)

- As mentioned before, the great general Marius made changes to the Roman army. Before the end of the Punic Wars, soldiers were still drawn from the masses of farmer-Plebeians. The Punic Wars lasted too long, and many soldiers returned home to find their farms either in shambles or actually sold from under them!

- Rome became flooded with poor masses of landless people looking for work in the city. They ultimately came to live in the infamous tenant buildings of Rome, which were disgusting and disease ridden. These hazardous buildings were always catching on fire. This landless poor became known as the Head Count. Since the Head Count were citizens, unscrupulous politicians (which was practically every politician) wooed them with bread, (the main food of the poor)entertainment, (gladiatorial games) and lots of empty promises.

- Marius was one politician who made one promise that became permanent. He offered a job for men with constant pay, equipment, and a retirement package (a pension and sometimes land at retirement). This job offer was to become a professional soldier.

- Marius was one tough cookie and disciplined the Roman army into an even greater fighting force than it had been before. His men had to carry about 60 – 80 pounds while marching, thus earning them the nickname, Marius’s Mules.

- Rome’s entire army eventually became professional. Soldiers served (by the time of Augustus) for 26 years! The pay was low. Julius Caesar became popular by doubling soldiers’ pay to 225 denarii a year. Of course, soldiers could be enriched by plunder if their general turned a blind eye.

- Marius was a fascinating man. He was called a New Man, since his family background was not noble, yet he was able to obtain great power and wealth. He utterly crushed a German invasion into Italy. He was consul seven times (five times in a row to deal with the Germans) and was called the Third Founder of Rome. He lived to be an old man, and it took three strokes to finally end his life. His wife’s name was Julia, and she was Julius Caesar’s aunt.

E. Marius’s Impact on Rome’s History

- Marius’s impact cannot be understated. For the first time in Rome’s history, soldiers became dependant on the wealth and generosity of their generals. Soldiers no longer returned to farms when the campaign was over. They went to live in the barracks and trained constantly.

- Roman generals suddenly offered Rome’s fighting men a future (if they could survive). Not surprisingly, legionaries became fiercely loyal to their generals. Roman generals weren’t stupid, and since political power and military power went hand-in-hand, power hungry generals salivated at the implications.

- If a general was rich, charismatic, and knew how to seduce the Mob and his own army into loving him, he could become infinitely powerful. Such a man was Julius Caesar.

Some Additions to the Military Made by Augustus

A. The Praetorian Guard

- Since the time of Sulla, Roman legions were not allowed in Rome or Italy. Augustus (Rome’s first emperor) made a change to this in 27 B.C. when he established a private body guard called the Praetorian Guard. These were elite soldiers (paid 2-3 times higher than a regular soldier) meant to protect the emperor from harm. The irony was that the Praetorian Guard sometimes murdered the very emperors they were supposed to protect.

B. Other Additions—Urban Cohorts and Vigiles

- Urban cohorts were basically policemen created by Augustus to protect the poor in the city of Rome.

- Vigiles were a fire fighting force created by Augustus.

- Urban cohorts and vigiles cannot be equated as being exactly the same as modern police or firefighters. These men were considered to be soldiers—of a type.

Warfare and the Transition to Empire

Rome’s Wars of Expansion

A. Conquering Italy

- As you already know, Romans were successful in expelling the Tarquins out of Rome in 509 B.C., but it would take about 200 years to rid Italy of Etruscan rule entirely, and the Romans didn’t do it alone.

- In 496 B.C. the Romans joined their Latin neighbors to form the Latin League, whose purpose was to fight the Etruscans.

- Not long after this union, the Etruscans were severely weakened by the Celts who were moving westward across Europe. They eventually settled in Gaul, (modern France)Britain, Ireland, and Scotland.

- The Celts briefly took a turn southward into Tuscany to plunder the Etruscans. Rome seized this opportunity in Etruscan weakness, and with the Latin League, defeated the last Etruscan stronghold in the city of Veii. From then on Rome would be the powerhouse in Italy.

- Unfortunately for the Romans, the Celts turned their attention toward Rome itself. In 390 B.C. the Celts defeated a Roman army and plundered Rome under the leadership of king Brennus. He demanded his weight in gold from the Romans. When they complained that the scales were fixed, he replied, “Vae Victus!” – Woe to the vanquished! It was the first time an enemy power would enter Rome. It would take over a thousand years before that would happen again.

- The Celts were not interested in conquering Rome and turned back northward to follow the migration into northwestern Europe.

B. No More Latin League

- Between 340 and 338 B.C., Rome turned on the Latin League and fought the Great Latin War to absorb its Latin neighbors.

C. The Samnite Wars

- Next, Rome turned southward on its Italic neighbors, the Samnites, who spoke a language called Oscan, which was similar to Roman Latin. By 290 B.C. Rome conquered the Samnites.

D. Taking the South

- King Pyrrhus of Epirus was the ruler of a hellenized kingdom on the eastern shore of the Adriatic. Around 280 B.C. Pyrrhus sailed across to Italy to help his Greek allies in southern Italy against the Romans.

- Although he won numerous battles against the Romans, he and his allies eventually lost the war. In winning one of his battles, Pyrrhus lost so many men that his victory was worse than a defeat. Since then, a disastrous victory has come to be known as a pyrrhic victory. By 265 B.C. the Greek city-states accepted Roman rule.

Mare Nostrum—Rome Takes the Mediterranean

The Punic Wars 264—146 B.C.

A. The First Punic War 264— 241 B.C.

- After Rome took southern Italy, it turned its attention to the island of Sicily, located off Italy’s southern tip. Sicily was known as a breadbasket, and Rome wanted the food it could provide.

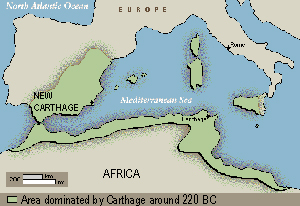

- Unfortunately for Rome, the Carthaginian Empire already controlled Sicily. Carthage, the capital city of the empire, was located near the northern tip of modern day Tunisia in North Africa. Carthage controlled Sicily, much of the coast of North Africa, (not including Egypt)and portions of Spain.

- Rome was determined to take Sicily from Carthage and declared war in 264 B.C. Just one problem faced the Roman military— it had no navy, and they had to have a navy if they planned to take an island.

- Undaunted, Rome set upon building a navy from scratch. As luck would have it, they came upon an abandoned Carthaginian warship and made hundreds of copies. They also developed a boarding technique whereby a Roman ship could grapple an enemy ship, enabling soldiers to board and use their land fighting techniques they knew so well.

- After some initial victories, Rome’s navy was devastated by storms that destroyed three fleets. A fourth fleet was built and in 241 B.C., Rome defeated Carthage. Rome took Sicily and made the Carthaginians pay a heavy tribute.

B. The Second Punic War 218-202 B.C. : Carthage Seeks Revenge

- Carthage was humiliated by its defeat in the First Punic War and swore revenge.

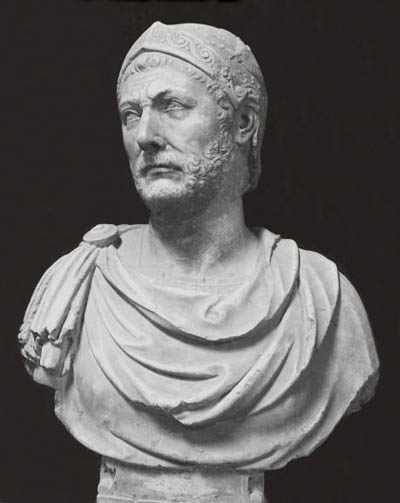

- Hannibal, a young and brilliant general, was given command of the Carthaginian army to exact the pain Carthage was bent on giving Rome. Hannibal was the son of Hamilcar. Hamilcar was the general partially responsible for losing the first Punic War. Hamilcar raised Hannibal to hate the Romans. He made Hannibal swear to get revenge.

- The Second Punic War began when Hannibal penetrated into areas of Spain where Rome had ties. Hannibal quickly defeated the opposition in Spain and began a laborious march with a huge army and about 50 war elephants.

- To get to Rome by land Hannibal had to cross the Alps in southern Gaul and northern Italy. Hannibal took his army through dangerous country. They were constantly harassed by local tribes and had to face a bitter winter. Many men and animals died. Hannibal had a will of iron, and through his leadership, his army entered northern Italy.

- In 216 B.C. two inexperienced Roman consuls decided to take Hannibal head on. At Cannae in eastern Italy Rome suffered one of its worst defeats at the hands of Hannibal. Seventy thousand Roman soldiers lost their lives, and 10,000 soldiers were sold into slavery.

- After Cannae Hannibal spent 13 years ravaging the Italian countryside. No Roman army could defeat him.

- It seemed Rome’s only advantage was that it controlled the sea and denied Hannibal the reinforcements and siege equipment he needed to attack Rome itself.

- Then in 203 B.C., the Senate appointed Scipio Africanus, to lead Rome against Hannibal.

- Scipio Africanus was a gifted general. He knew the only way to beat Hannibal was to take risks. So, instead of fighting Hannibal in Italy, Scipio took his army across the Mediterranean to Carthage and placed Carthage under siege. Carthage held out, but it was not prepared for a direct attack and forced Hannibal to return to defend it.

- Hannibal and Scipio met in the battle of Zama, a few miles away from Carthage. At Zama Scipio defeated Hannibal’s army. Hannibal escaped from Zama, but he was constantly pursued. He eventually committed suicide by drinking poison.

- Carthage was forced to give Rome all its territory in Spain, pay a heavy tribute, and agree to limit its navy to only ten ships.

C. The Third Punic War 146 B.C.

- Rome never got over what Carthage had done to its army through Hannibal. This time, Rome sought vengeance.

- In 146 B.C., Rome sent an army to lay siege to Carthage. Carthage held out for six months. In the end, every Carthaginian was either killed or sold into slavery. The city was razed to the ground, and salt was sown into its fields. Rome took all of Carthage’s remaining territory in North Africa, and began calling the Mediterranean, Mare Nostrum (Our Sea).

The Collapse of the Republic 146—59 B.C.

A. Society of the Late Republic

- As mentioned before, after the Punic Wars, soldiers returned home to find their farms in ruins or sold from under them. They and their families became Rome’s urban poor— the Mob.

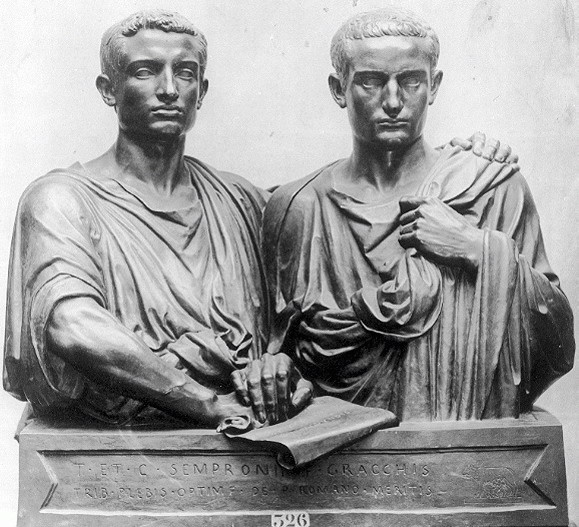

- Many politicians equated the fate of these people with the decline of the Republic. Two brothers, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, tried to force the Senate to help the poor. They each became tribunes at separate times, and tried to enact land reform through their power in office. These brothers were the grandsons of Scipio Africanus.

- They were immensely unpopular with the Senate, because Tiberius and Gaius wanted to divide up land that belonged to Senators to the landless poor. They both wanted to make Rome’s Italian neighbors citizens. In 100 B.C., Tiberius Gracchus was beaten to death with a bench on the steps of the Capitol Building during a staged riot by the Senate. Ten years later, when Gaius Gracchus was tribune, he tried to enact the same reforms as his brother. Gauis Gracchus was forced to commit suicide when it was clear he would soon be murdered in another riot. Gauis had his personal slave stab him to death. A political solution to Rome’s problems within the confines of the traditions of the Republic was not possible.

B. Marius

- As mentioned, the general Marius had a solution that worked for many men. He made them professional soldiers.

- Marius was elected consul five years in a row (104—100 B.C.) to deal with German incursions into Roman territory. He was very effective in battle, and carved out new territory for Rome. He gave his retired soldiers land in the newly conquered provinces.

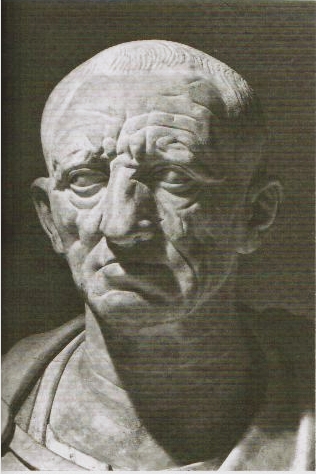

C. Sulla

- The next general to come onto the scene was one of Marius’s former officers, Sulla. Sulla became consul in 88 B.C. and was sent to deal with king Mithridates, who was trying to carve out a Hellenistic empire for himself in Asia Minor. Mithridates would be a pain in Rome’s neck for many years to come.

- Sulla was successful in stopping Mithridates’s encroachment into Rome’s interests. He began his return to Rome in 83 B.C., only to learn that his enemies in Rome were plotting against him. Sulla marched his army into Rome (he was the first to do this), and had his enemies murdered. Out of fear of further reprisals, the Senate proclaimed Sulla dictator.

- While dictator, Sulla remade much of Rome’s constitution. He designed a new judicial system, increased the size of the Senate, and increased the Senate’s power. He greatly reduced the power of the Tribunes, and removed their right to Veto in most instances. Some of these reforms were liked, but many were revoked after Sulla’s death. He remained dictator from 82 to 79 B.C. In 79 B.C., Sulla retired from power and died the following year. He supposedly died a rather unpleasant death. Some people even spread stories that worms ate his insides, and that’s what killed him!

The New Boys in Town: Pompey, Crassus, and Cicero

A. After Sulla, it became the goal of ambitious politicians in Rome to get a military command, and draw wealth and power from it.

- Pompey, one of Sulla’s former officers became the leading general and politician. His chief rival was Crassus, who grew fabulously wealthy through questionable real estate dealings.

- Pompey began making a military name for himself, in 71 B.C., by putting down a rebellion in Spain.

- Crassus became famous for putting down Spartacus’s slave rebellion.

- Conflict was avoided between the two generals when they were both made consuls in 70 B.C.

B. Cicero, a Self-Made Man

- Cicero was a member of the equestrian class, who through extraordinary skill in public speaking and intellect, rose quickly in government. In 63 B.C., Pompey helped Cicero become a consul out of gratitude for Cicero throwing his political support to Pompey over Crassus.

- Crassus searched for a supporter who would get him back into power. Pompey had Cicero. Crassus found Julius Caesar.

The End of the Republic 59—30 B.C.

A. The Rise of Caesar 59 —52 B.C.

- Julius Caesar was a member of a very old Patrician family. He had won great popularity with the Roman Mob, and accrued great debt to win their political support.

- Crassus paid Caesar’s debts, and helped him gain rapid political advancement.

- Caesar could be very convincing, and convinced Pompey to join him along with Crassus (in 60 B.C.) to form a triumvirate—or military rule through three leaders. This was Rome’s First Triumvirate. Caesar won a consulship the next year.

B. The Gallic Wars 58—53 B.C.

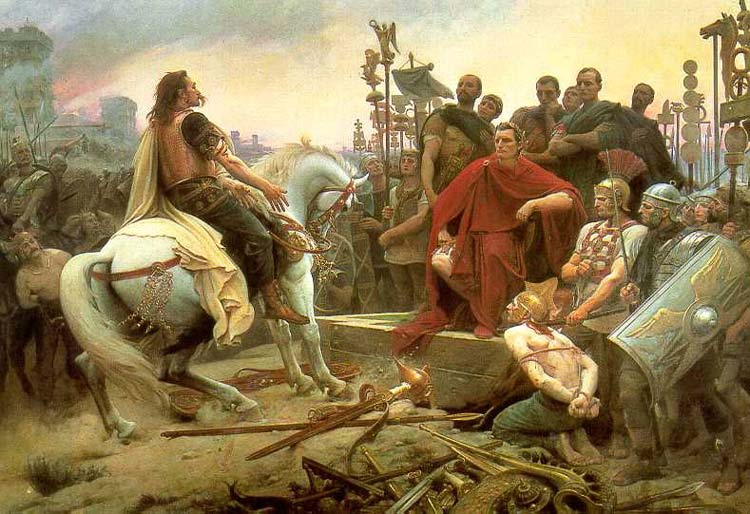

- Caesar knew that to obtain real power he needed an army. In 58 B.C., Caesar received a five-year proconsular command, later doubled in length to pacify rebellious Gauls in Roman territory. Caesar put down the rebellions, and kept on going. He conquered all of Gaul and even made military expeditions into Britain. His greatest challenge came from Vercingetorix, a Gaulish chieftain who managed to unite several tribes against Caesar. Vercingetorix surrendered in 53 B.C. He wanted to end the bloodshed of his people.

C. Crassus Gets Stomped

- Crassus also received a military command against the Parthians in the east. Although Crassus had defeated Spartacus many years before, he wasn’t the best general.

- The Parthian army utterly crushed Crassus’s army. Crassus was decapitated, molten gold poured down his detached throat (to mock his wealth), and his hands cut off for props in a play performed before the Parthian emperor. This left only Pompey and Caesar in power. They quickly grew jealous of each other, and became enemies.

D. Caesar Comes up on Top

- The Senate tried to end Pompey and Caesar’s feud by requesting they both give up their military commands. When Caesar refused, the Senate ordered Pompey to march against him. Rome became torn by civil war from 52 to 48 B.C.

- Caesar defeated Pompey at Pharsalus in 48 B.C. Pompey fled to Egypt. The Ptolemaic king beheaded Pompey, hoping by doing so he could win Caesar’s favor. Caesar did not appreciate the effort.

- Caesar stayed in Egypt for a while and had an affair with Queen Cleopatra. They had a child together: Caesarean.

Julius Caesar: Dictator Perpetuus

A. The Rise and Fall of Julius Caesar

- In 45 B.C. Caesar was named dictator. Although this was a Republican title, everyone knew power was shifting from the Senate to Caesar. Caesar held the imperium over the entire Roman army, and through sheer force could get anything he wanted. Caesar immediately sought to reform Roman corruption. He gave soldiers land and changed the Roman calendar (to be called the Julian Calendar) to have 365 days a year with an additional day every four years. This was a copy of the Egyptian calendar. In the Middle Ages, Pope Gregory refined the calendar further. This final version is called the Gregorian Calendar. We use the Gregorian Calendar.

- In February 44 B.C., Caesar was given the title dictator perpetuus, or dictator for life. This was too much for his enemies who still resided in the Senate.

- A conspiracy led by senators Brutus and Cassius was hatched to murder Caesar. On March 15, 44 B.C. (The Ides of March), Caesar was stabbed to death on the Senate floor. He died at the foot of a statue of Pompey.

The Second Triumvirate and Empire

A. Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus

- These three men joined together to form the Second Triumvirate in 44 B.C. Octavian, who was Caesar’s grandnephew, was Caesar’s heir. Mark Antony and Lepidus were former officers under Caesar. They sought to extract revenge from Brutus, Cassius, and the other conspirators who murdered Caesar. In 42 B.C. the last of the conspirators had been beaten.

- From then on, Rome found itself in another civil war between Octavian and Antony. Lepidus retired from power, under Octavian’s prompting.

- Antony went to Egypt and joined Cleopatra there. Antony was completely enraptured by Cleopatra. He went so far as to promise parts of Roman territory to her. Antony became extremely unpopular in Rome. Octavian campaigned against Antony and defeated Antony’s forces in the naval battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide.

- Octavian was now without rivals. In 30 B.C. he became the most powerful man in the western world. He, however, proclaimed the restoration of the Republic in 27 B.C. and retired from power. This was a masterstroke. He didn’t want jealous senators to kill him, like they had Caesar. He was a political genius, and knew if he were patient, the Senate would be on its knees, begging him to return to power. He was right.

- The Empire was in shambles from years of civil war. The Senate could not fix these problems. They needed a leader, and begged Octavian to return to power. He always behaved modestly, and pretended like he really never wanted all the honors and titles the Senate bestowed upon him. One title, augustus, “most revered” he kept. Octavian changed his name to Augustus. Augustus became Rome’s first emperor. His rule became known as The Principate of Augustus. He ruled from 27 B.C.—14 A.D.

- The Roman Empire in the west lasted until 476 A.D. It would have many good emperors and many bad emperors.